December 25, 2009

November 3, 2009

I'LL BET YOU KNOW THE TYPE OF PEOPLE HE'S WRITTEN ABOUT!

John Betjeman (1906 - 1984)

Here's one of my favorites:

How To Get On In Society

Phone for the fish knives, Norman

As cook is a little unnerved;

You kiddies have crumpled the serviettes

And I must have things daintily served.

Are the requisites all in the toilet?

The frills round the cutlets can wait

Till the girl has replenished the cruets

And switched on the logs in the grate.

It's ever so close in the lounge dear,

But the vestibule's comfy for tea

And Howard is riding on horseback

So do come and take some with me

Now here is a fork for your pastries

And do use the couch for your feet;

I know that I wanted to ask you-

Is trifle sufficient for sweet?

Milk and then just as it comes dear?

I'm afraid the preserve's full of stones;

Beg pardon, I'm soiling the doileys

With afternoon tea-cakes and scones.

You may want to read a short biography--well worth your time.

ir John Betjeman (1906-1984), Poet Laureate of Britain from 1972 to 1984, was the most popular English poet of the 20th century and a familiar personality on British television.

John Betjeman was born in London on August 28, 1906, the only child of a prosperous silverware maker of Dutch descent. A sensitive, lonely child, he knew early that he would grow up to forswear the family business in favor of poetry. He attended prep school at Highgate, London, where one of his instructors was a recent American arrival, T. S. Eliot, who proved unresponsive to the 10-year-old's poetic efforts. During his tenure at Dragon School, Oxford (1917-1920), Betjeman developed an abiding interest in architecture; he next attended Marlborough public school in Wiltshire, which he was to remember chiefly for its bullies.

He entered Magdalen College, Oxford, in 1925 and favorably impressed the great classics scholar C. M. Bowra with his knowledge of architecture, but negatively impressed his famous tutor C. S. Lewis by his academic indifference. At Oxford he struck up a lasting friendship with Evelyn Waugh and may even have served as a model for one or more of the characters in Waugh's early novels; more importantly, Betjeman cultivated at Oxford a strong aversion to sports and an equally strong inclination towards esthetics. He left Oxford in 1928 without a degree.

Early Career

Betjeman taught briefly at Heddon Court School, Hertfordshire, and then worked for a while as an insurance broker before becoming, in 1931, an assistant editor of the Architectural Review. That same year he published his first book of verse, Mount Zion. Although somewhat mannered and certainly minor, the collection was distinguished by at least one poem, "The Varsity Students' Rag," which quietly but effectively satirizes the mindless, boys-will-be-boys destructiveness of his former fellow Oxfordians.

In 1933 Betjeman became editor of the Shell series of topographical guides to Britain and married Penelope Chetwode, a writer by whom he had a son and a daughter, but who pursued her own writing career abroad for most of their married life. In 1934 he became film critic for the Evening Standard but was fired less than a year later for his overly enthusiastic reviews. Betjeman's second volume of verse, Continental Dew: A Little Book of Bourgeois Verse (1937), is undistinguished but for its foreshadowing of an attitude that was to fully surface in subsequent books: a deep-dyed distrust of "modernity" in all of its guises - its indifference to tradition, its runaway materialism, and its savaging of the landscape.

Betjeman's book titles and sub-titles are frequently thematic, as in his first book on architecture, Ghastly Good Taste: a depressing story of the rise and fall of English architecture (1933); it was followed by University Chest (1938) and then Antiquarian Prejudice (1939), which defines architecture for Betjeman as not mere building styles but as the total physical environment in which life is lived. His topographical writings, which celebrate actual places he loved and excoriate places he loathed, include Vintage London (1942), English Cities and Small Towns (1943), and First and Last Loves (1952).

Major Career

During World War II Betjeman served variously as United Kingdom press attaché to Dublin, as BBC broadcaster, and in the British Council books department. In this period he issued two volumes of verse that revealed him to be a serious poet and not a mere "versifier": Old Lights for New Chancels (1940) and New Bats in Old Belfries (1945). Although they share with most modern poetry a profound pessimism about life, these works established Betjeman as a distinctive voice and somewhat of an anomaly: in an age dominated by lyric-contemplative verse, Betjeman relied strongly on narrative, or at least anecdotal, elements; in an age of free verse, he wrote in tight metrical and stanzaic forms; in an age of poetic obfuscation, Betjeman, though not without his ambiguities, was accessible; in an age of tight Classical control of emotion, he was wistfully playful and even sentimental. In short, Betjeman was a throwback to the best-loved poets of English verse tradition - to Tennyson, Hardy, and Kipling.

In both volumes Betjeman made humanly evocative use of place (many of his poem titles are place names), reflecting the importance of topography in his work and projecting his thesis that as the landscape grows uglier the possibility of human happiness recedes. Both volumes sold well and were favorably reviewed, but Betjeman's reputation as an architecture and topography writer still outstripped his reputation as poet.

In the 1950s Betjeman continued to write prolifically on architecture and topography, produced a book of verse - A Few Late Chrysanthemums (1954), and did a year of BBC broadcasts (1957). Most important, he published his Collected Poems (1958), which was a huge seller, an astounding fact considering normal public indifference toward poetry and the consequent well-known indigence of almost all poets.

His popularity was enhanced by a blank-verse autobiographical poem, Summoned by Bells (1960), a quiet, introspective account of his first 22 years, and by two more verse collections, High and Low (1966) and A Nip in the Air (1975). Sandwiched between, in 1969 Betjeman was knighted and in 1972 he was appointed Poet Laureate of Britain.

Reputation and Last Years

His public acclaim notwithstanding, Betjeman had his detractors among poets, critics, and scholars, many of whom found him shallow or facile and branded him a Tory traditionalist or an English provincial or a hopeless antiquarian. His defenders and admirers, however, included Edmund Wilson, W. H. Auden (who dedicated The Age of Anxiety to Betjeman), and Philip Larkin.

A London journalist once described Betjeman as "looking like a highly intelligent muffin; a plump, rumpled man with luminous, soft eyes, a chubby face topped with wisps of white hair and imparting a distinct air of absentmindedness … [with] an eager manner, a kind of old-fashioned courtesy and a sudden, schoolboy laugh which crumples his face like a paper bag."

Poor health curtailed Betjeman's writing efforts in his later years, but what energies he had were dedicated to his continuing campaign for the preservation of historic buildings. After suffering from Parkinson's disease of a number of years, Betjeman had a stroke in 1981 and a heart attack in 1983. He died on May 19, 1984, at his home in Trebetherick, Cornwall, attended by his companion of many years, Lady Elizabeth Cavendish.

Courtesy of Biography Online

November 1, 2009

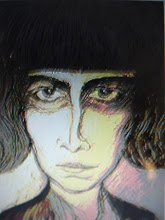

SUI GENERIS: CECIL BEATON

It would seem that art, however important,

is not life itself: and to set up a code of "art for art's sake"

can at times prove equally as inhuman as any political dogma which is fostered and held above human values themselves.

October 26, 2009

So What If You Think Luisa Was Just Another Aristocratic Tramp

June 14, 2009

SUI GENERIS: GRETA GARGO

June 12, 2009

TOO BEAUTIFUL FOR WORDS--Gypsy Strings

I emerged from the haze of studying something like "Boggle Your Friends With Your Command of Italian," when I realized that I had become completely enraptured by the gypsy violin music that was playing. The piece was "Bulgarian Lament" from Gypsy Strings, Adam Summerhayes and Bulgarian violinist Emil Chakarov, (The London Concertante, Chandos 2008). (Perhaps I should be contemplating studying Bulgarian--or at the least, learning to dance like a gypsy) Truly a haunting and sensual work.

More than once in the last couple of years I have had the good fortune to attend performances by the extraordinary band that trades under the name of ‘Zum’, a band which fuses Eastern European gypsy music with the Argentinian tango, elements from jazz and much else (salsa, klezmer, Irish fiddle music – you name it!). A leading spirit in that band (make sure that you get to a performance if you possibly can) is violinist Adam Summerhayes. Summerhayes is an accomplished classical violinist and on this present recording he is joined by Bulgarian Emil Chalakov, another classically trained violinist with a passion for gypsy fiddling. One of Summerhayes’s several musical hats is worn as leader of the London Concertante, and it is the twelve strings of that fine chamber orchestra which support thtwo soloists in this compelling and entertaining selection of thirteen numbers . . .

. . . This is a CD to raise the spirits, full of energy and commitment, richly expressive and inventive, but rooted in age-old traditions, traditions which Summerhayes re-presents in a fashion that is both respectful and original. Whether you already love the gipsy music of Bulgaria and Romania and are happy to see it reinterpreted in a distinctive and accomplished fashion in which the players are true to themselves as well as to their sources; or whether you value fine violin playing whatever the musical genre; either way this is a CD sure to give you lots of pleasure.

June 4, 2009

"I WANT TO BE A LIVING WORK OF ART"

Much of my time ferreting into the life and times of the inimitable Marchesa Luisa Casati was spent tracking down innumerable references to her. (In my mind I was already calling her Luisa). I found her name popping up in the oddest places. Being seduced by what I thought of as clues to her enigma, I was drawn deeper and deeper into Luisa. (In fact, I began to imagine that people were whispering about her at cocktail parties.) There are some people whom you think you know absolutely everything about, but you wake up one day to find you never understood their essence. They possess the quality that the French call le mystere. You're either born with it or you're not. C'est la vie, mes petits choux

Rummaging through my notes and examining my personal feelings about her, I found her fascinating, yes, but I couldn't decide whether she was a sympathetic creature or a repellent one. But then I realized that I didn't care-- I DIDN'T CARE --because as with everyone else who fell under her spell, I was mad for her--mad to know her, mad to be her--and no hope for either one, alas. Because Luisa Casati was the most devastating femme fatale of the early years of the twentieth century. She was not merely a celebrity--she was the real thing.

Luisa was born in Milan in 1881 into wealth and luxury. Her childhood was uneventful (by the standards of childhood). Her mother died young and when her father followed when she was sixteen, she and her elder sister became the wealthiest heiresse in Italy. A few years later she was married to Camillo Casati Stampa di Soncino, Marchese di Roma. After the birth of a child, the Marchesa and the Marchese separated. Luisa would now begin to fulfill her destiny.

Traveling throughout Italy and France, with a particular penchanant for Capri, Luisa collected palaces like charm bracelets. Around 1910 she settled in Venice, where she installed herself and her growing menagerie of exotic animals in the semi-ruined Palazzo Venier dei Leoni on the Grand Canal (later called home by Peggy Guggenheim--another notable Bohemian--and currently the Peggy Guggenheim Collection). Around that time Luisa began a passionate love affair with the then famous Italian lover and poet, Gabriele D'Annunzio, which lasted on and off for years. Exclusivity was hardly expected in their set, and Luisa simultaneously enjoyed love affairs with both men and women. Her scandalous indulgences had no effect on her fassinated hordes of admirers.

Luisa's guests must have stood by in jaw-dropping awe at the spectacle of her Nubian servants naked and gilded, holding great flaming torches at the entrance to her Palazzo. The Marchesa would greet them bedecked and bejeweled with live snakes. Guests would find her dinner table occupied by full-sized figures carved of wax--supposedly her lovers--slowly, slowly melting from the heat of the masses of candles on her long dinner table. Can you imagine the splendor of her impossibly extravagant masquerades, her grand receptions for Diaghelev, Nijinsky and the Ballets Russes-- all the while her cheetahs prowling in a midnight garden illuminated by red and gold Chinese lanterns.

Very tall and long-limbed--and of course very, very rich--the Marchesa scandalized (or secretly delighted) Venetian society by her late night soujourns through the Piazza San Marco. Naked under a long fur coat, she was accompanied by her two pet cheetahs straining at the end of their gem-studded leashes. (In fact, late one impossibly cold and damp winter night when I lived in Venice I thought I caught a glimpse of her with her spotted cats slipping through the Piazza before she disappeared under the Clock Tower. (But I had been celebrating my birthday with friends at Harry's Bar and it was Venice, after all.)

Luisa indulged herself in the outrageously sublime couture of Mario Fortuny, Paul Poiret and Erte. Fascinated with the mystical, the Marchesa upended the aristocracy when they listened to rumors of her opening her palazzo to various seers and psychics --as long term house guests! Bizarrely compelling in her exotic garb, accessorized with 'living jewels,' the palor of her skin like moonlight--not to mention her huge green eyes and marmalade-colored hair--she effortlessly commanded her audience.

After Cleopatra and the Virgin Mary, it has been said that Luisa was probably the most painted, sculpted, drawn and photographed woman in art (even if she herself commissioned many of the representations). Indeed, our Marchesa was possessed by a passion for the arts. She gave far more than great financial support and patronage---she gave her presence. At events artistic and literary people thronged about her, attempting to catch a glimpse. Luisa's house in the environs of Paris, the Palais Rose, with a private art gallery, contained more than 130 paintings of her likeness (and how many mirrors, I wonder). She posed for ManRay, Cecil Beaton, Kees Ven Dongen and Boldini among so many others. The English painter and infamous lover Augustus John became Luisa's lover and she his muse. He painted one of his greatest portraits of her but was unable to bend her will to his. He would tell anyone who listened, "Luisa Casati should be shot, stuffed and displayed in a glass case." Luisa's response is unknown as she had already drifted off with other artists, aristocrats and literati who worshipped at her feet.

Sadly, not all fairy tales end in 'happily ever after.' The cost of indulging Luisa's unrestrained desires finally exhausted her great fortune. What must she have felt to realize that at only 49 years old she was $25 million in debt? What would she do with the rest of her life? Was the party finally over? What could she do? An auction of all her possessions ensued--with notable figures such as Coco Chanel among the avid bidders. (I imagine a room full of well-dressed vultures all wanting a piece of her).

Luisa retired to London and lived in relative obscurity and not-so-genteel poverty for the next thirty years. Among others she was consoled in her exile by visits from the writer, raconteur and future gay icon Quentin Crisp, the art historian, aesthete and dandy Philippe Jullian and the eccentric composer Lord Berners who stopped by for tea. It almost brought me to tears to read that there were rumors of her seen rummaging through trash bins late at night searching for feathers to put in her hair. (If I am ever in similar circumstances, I shall do the very same thing in her honor).

Age shall not wither her nor custom stale her infinite variety, from Shakespeare's Anthony and Cleopatra was engraved upon her tombstone in Brompton Cemetery in London when the grand Marchesa Luisa Casati died in 1957.

For those interested in further exploring the Marchesa Luisa Casati, I suggest you read her definitive biography, Infinite Variety: The Life of the Marchesa Luisa Casati by Scot D. Ryerson and Michael Orlando Yaccarino; "The Other Heiress: The Marchesa Luisa Casati" by Lorette C. Luzajic (www.thegirlcanwrite.com) The Glass of Fashion by Cecil Beaton; Phillippe Jullian, Vogue September 1970; and follow up any references to Luisa that you come across. Please let me know should you find something interesting.